This post is about civil war history, but it’s also written as a memento for my youngest son to remember our trip by.

In great deeds, something abides. On great fields, something stays. Forms change and pass; bodies disappear; but spirits linger, to consecrate ground for the vision-place of souls. And reverent men and women from afar, and generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field, to ponder and dream.

— Joshua Chamberlain at the Dedication of Maine Monuments, Gettysburg, PA, October 3, 1888

***

Last October 29, 2016, I visited the Gettysburg battlefield with my friend Rich and my youngest son. It was a beautiful autumn day. The temperature was perfect. The skies clear. The colors were at their peak. It was a lovely day to reflect and daydream.

Like with any meaningful place, there’s a unique spirit-of-place to Gettysburg that stills the soul and leaves a lingering presence, haunting the corners of your mind long after you’re gone.

The impetus for this particular trip had three things behind it:

First, my love for history and biography. I’ve read and learned a lot about the Civil War and the leading characters of this epic historical drama. The battle of Gettysburg was the biggest, mostly costliest battle ever fought in this hemisphere. At the end of 3 days of savagely intense fighting, there were upwards of 51,000 casualties between the two armies. Consider that just for a moment. Over an approximately 72 hour period, there were almost as many casualties incurred at the Battle of Gettysburg as there were U.S. troops killed (59,000) in the entire 10 years of the Vietnam War. For any student of American history, you can’t learn enough about the Civil War or what happened at Gettysburg and how it changed the direction of American history and the shape and trajectory of our nation leading up to the present. There are many great books out there, but I suggest you begin with the best. The Civil War historians Bruce Catton, Shelby Foote, and James M. McPherson have produced some of the finest literary histories ever written. Stephen Sears wrote one of the best, most comprehensive histories of the Gettysburg campaign. And who can forget the absolutely absorbing, pulitzer prize winning, historical novel by Michael Shaara, The Killer Angels, and the movie based on it. There’s a lot of great literature about the Civil War. Any aspiring writer can learn his or her craft just by reading Catton, Foote, and McPherson alone.

The study of war is so much more than a study of strategy, maneuvering, and the calculated application of violence. The history of warfare (as does all history) teaches us many things, but it’s an especially good tool for teaching leadership, whether it’s for the personal or professional domains of our lives. Violence, to be sure, is the shroud of war. But within this covering fabric is the vast interweaving of human qualities, both base and noble. To study and learn from this collision of circumstance and character is one of the best educations in human nature, human excellence, and human folly you’ll ever get. “History is,” Lord Bolingbroke once said, “philosophy teaching by example.” Hopefully this type of liberal education, as it was intended, inspires each of us to emulate the virtuous and the noble—to be guardians of civilization and civilized values. An education in any of the Liberal Arts is ultimately about improving the heart and mind, but historical study in particular provides the best laboratory for examining what human beings have actually done, said, and suffered. Literature, historical or otherwise, has the potential to greatly expand our empathetic and intellectual horizons. It’s a never ending journey of discovery. It has the potential to positively transform your life.

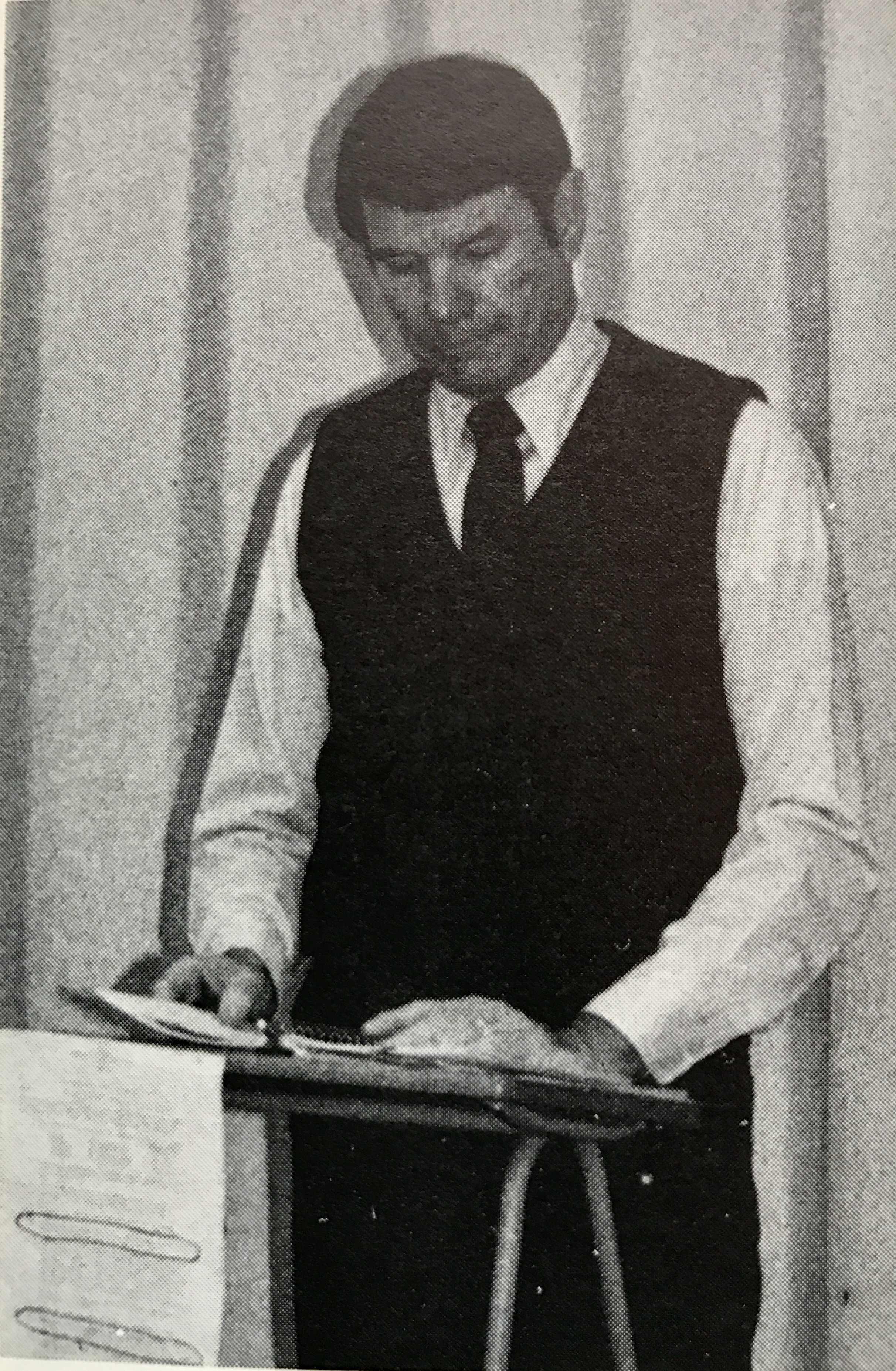

This brings me to a brief aside. I think it’s important to remember the great teachers of our life, those who helped form who we are today. I date the beginning of my lifelong fascination and love for history to my time in Donald Fuller’s history class at Kempsville Junior High School (now Kempsville Middle School) in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Don Fuller was a retired Naval Officer and teaching was his second career. He had a real passion for teaching and he really knew how to make history interesting and relevant to my understanding of the world. I can still remember how I’d approach him after class to get more details about a famous person, battle, or event that he’d discussed during class. He would take his time with me and often draw on the chalkboard to illustrate his point. I can still remember him drawing the details of Hannibal’s “bending bow” strategy at Cannae. He knew so many interesting things about the battle and the characters involved. I remember being fascinated by the depth and breath of his knowledge, and thinking to myself how I’d like to be that knowledgeable about history one day. I can still recall the sound of his unique voice. About a decade or so after attending his class, I visited him at Kempsville Junior HS, where he was still teaching. He remembered me at first sight and was glad to see me. We had a good long talk standing in the hallway. He was still the teacher, and I was still the admiring student. He was a big influence in my early life and certainly a big reason History has been one of the passions of my life. In its original Latin derivation, the word inspire means “to breath into,” and that is what Don Fuller did for me. He inspired me. I really admired him, and I will never forget him.

Secondly, I also wanted to visit Gettysburg because my good friend Rich had never been there, and he wanted to take some pictures (I didn’t know at the time, that another motive for Rich wanting to go was his secret mission to help get me out of the house so my lovely wife could prepare for my surprise birthday party, that afternoon, when we got home!). And lastly, but most importantly, I wanted to go to Gettysburg so I could spend some quality time with my youngest son, Seth. This would be his first trip to Gettysburg and hopefully one among many to historically significant places over his life.

Our first stop that morning, after touring the visitor center (where I bought my son a toy musket and canteen), was the federal army’s position along Cemetery Ridge. Union or federal army troops had retreated to this position (the high ground) and formed defensive lines during the 1st day of battle (It was a 3 day battle, July 1-3, 1863).

The battlefield, especially the federal army side, is replete with monuments and memorials. The largest and most impressive is the Pennsylvania memorial. All around the outer edge of this massive stone structure are large bronze tablets with the memorialized names of approximately 34,000 officers and soldiers from the Pennsylvania regiments that fought in the battle.

While walking around the Penn memorial, Seth and I discovered that it had an upper level for viewing the battlefield, so we headed up. My son was nervous about being up so high. He leaned against me protectively and held my hand tightly, as we climbed the narrow spiraling stairwell. As we continued up I heard his shaky voice, slightly strained with fear, say “I’m afraid of heights dad.” I’d never heard him say this before, so I pulled him closer and we continue up. We emerged onto a circular viewing platform and a magnificent view. From this position we were near the center of the federal army line. To our south the line runs to Little Round Top—the far left end of the federal army line— and then turning our gaze northeasterly, we saw Culp’s Hill, which is the far right end of the federal army line. Directly to our West was the confederate army position in a tree line along Seminary Ridge.

We lingered a little while and I took some pictures. We waved to Rich who was still in the parking lot below getting his camera equipment together. He took a picture of us waving from the top of the memorial. My son didn’t want to linger, so we walked around the memorial dome, taking in the view from all sides, and then headed back down.

We moved from the Penn memorial to another part of Cemetery Ridge known as the “bloody” Angle. This is the point confederate General Robert E. Lee focused his main attack on the afternoon of July 3rd at about 3 p.m. Known as Pickett’s Charge, it was comprised of between 13,000 and 15,000 men, mostly Virginians, and was ultimately repulsed (with over 50% casualties), but not before a brigade of Virginians led by Brigadier General Lewis Armistead breached the federal line at the Angle. Armstead’s men fought bravely, but there simply wasn’t enough of them to exploit the breakthrough. There’s a plain stone marker at the spot where Armistead was hit and fell during the close quarter fighting. That spot is known as the High Watermark of the Confederacy.